Recently on a teacher discussion board I follow, some

teachers were discussing the new trend of “take apart” or “tinkering” centers

and how overwhelmed they felt trying to manage those activities in their

classrooms. “Take apart” isn’t actually a new trend, but the current push

toward emphasizing STEM (or STEAM or STREAM) activities has pushed the old

tools and woodworking activities into the spotlight. The teachers on this board

felt pushed to provide science and technology activities, but were struggling

with how to do it in a child-directed play based way that ensured children’s

safety. They were concerned about physical safety – children using tools like screwdrivers,

wrenches, and wirecutters safely. But also about emotional safety – one of the

common concerns mentioned was how easily the children got frustrated trying to

take out screws or untangle wires. Several teachers said the activity ended

with children hitting and banging the materials against the table, or smacking

them with the screwdriver.

One of the things we sometimes forget in play-based

curriculum, is that teachers are there to teach. We can follow children’s lead,

and build curriculum around their ideas, but in our role as experienced adults,

we can also provide the scaffolding and guidance they need to develop skills

and to learn the steps needed to accomplish tasks independently. “Take apart”

(or using tools) doesn’t involve a natural process like gravity or flotation

that can be discovered through observation or trial and error. It involves a

complex set of visual motor skills and use of human designed tools. Some

children can figure some of these skills out independently, but some need scaffolding

– adult guidance to help them complete the task successfully with as much

independence as possible.

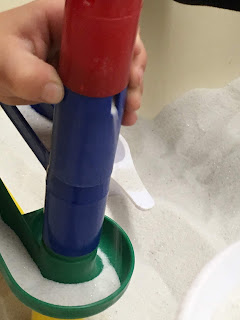

Before embarking on a take-apart project in my four-year-old room, I wanted to give the children an opportunity to explore and practice with the tools they would be using. I bought several different sizes of Phillips and flat-head screwdrivers, and a variety of large screws with wide heads. I put these out on a table with large pieces of Styrofoam, and inserted several of the screws into the Styrofoam. I showed the children the screwdrivers, and asked them if they could figure out how to screw and unscrew the screws.

Some of them had worked with screwdrivers before. Some hadn’t. One of the

children noticed the difference between the flat head and Phillips head screws.

I suggested they try both types of screwdrivers, and see if the same

screwdriver worked on both screws. They figured out right away that they didn’t,

but I wonder if they would have noticed this important difference if I hadn’t

encouraged them to experiment.

After a few days of working with screws and Styrofoam,

with a teacher participating alongside them, it was time to move on to “take

apart.” My co-teacher brought in an old cassette player, and we loosened the

outside screws ahead of time, so the children would be able to unscrew them on

their own. My co-teacher worked alongside them, to help hold the cassette

player, or help turn a screw that they were having trouble with, and to simply

manage the area, helping them to negotiate turns and to pass the materials

around the table.

When they finally opened the case, figuring out what was inside wasn’t nearly

as interesting to them as taking it all out.

The most interesting discovery about the contents was

that the speaker was magnetic, and each child tested this by sticking their

screwdriver to it. What a speaker is, and why it’s magnetic, wasn’t even a

question – they were focused on the process of sticking metal pieces to the

magnet

After everything was taken out, I asked if they thought they could

put it back together. At that point, several of the take apart crew had left,

because when you’re four, taking things apart is usually more interesting than

putting it back together. But two of the children stayed with the project, and

with my help, figured out how to close the cassette player case and fit the

screws back in.

Did they figure this all out independently through

play? No. Did they follow step by step directions and learn how cassette

players work? No. But someplace in between completely child driven and

completely adult led activity, they explored, they observed, they predicted,

and they problem solved. Which is what science is all about – with our help.