Early childhood education can sometimes get caught

between two extremes. On one side there are teachers armed with lists of

standards and objectives, tailoring every experience to instruct children in a

specific skill. On the other side there are teachers who say they just sit back

and watch while the children learn all they need to without adult interference.

The reality of learning is someplace in between. Children learn through meaningful

experiences and interactions that allow them to construct their own knowledge

and build understandings about their environments through play. But adults are

the ones who control that environment. Whatever materials are there for children

to play with are there because an adult provided them.

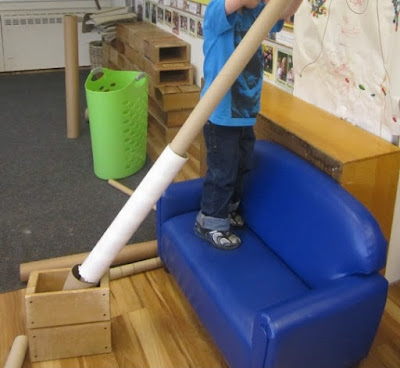

“Just put out the materials and let the children decide what to do with them.” Statements like this reflect the wonderful power of child-directed play and exploration, but they also ignore the adult’s role. What does “just put out the materials” mean? Are they on a table or on the floor? In a basket, on a tray, or in a pile? What are the materials, and how did they get into the classroom? What is the teacher doing or saying while the child explores? While trying to value and embrace child-led learning, teachers sometimes sell themselves short, and forget that every aspect of the classroom involves some decision making by the adult. The key to creating environments where children can direct their own learning is for the adults to make these decisions in an intentional way.

Objects can have social meaning and visible physical

properties that impact how we think of them. We approach objects based on our

previous experiences and knowledge. Containers can be filled and emptied. Rounded

objects roll. Shaking and banging create sounds. Colors change their appearance

in shadows and light. Children aren’t blank slates. Every interaction they have

is built on the history of all the interactions that came before, as they

experiment, explore, and build understandings of their world through play.

This is where adults can come in. Not by telling

children what they should do with the

materials, but provoking the spark of what they could do with them. By making intentional choices of what materials

to have in a classroom, and how to present them to children, teachers can provoke

children to think “What can I do with this?” We can plan classroom environments and present materials that spark children’s creativity, initiative, and

innovation, not by giving direction, but by presenting provocation. Intentional

teaching is partnership with children. It’s collaboration and communication. Intentional

teaching is the adult saying. “I see your wonderful idea. Let’s travel there together.”