I’m always looking for new ways for children to move sand and

water in the sensory table. Most of the time, sensory table activities focus on

the basic activities of scooping, filling, and pouring. As children get older,

and gain more experience with these tasks, they become less interesting. You

can only scoop and pour so many times before you’ve mastered it and are ready

to move on to exploring and manipulating the materials in a different way.

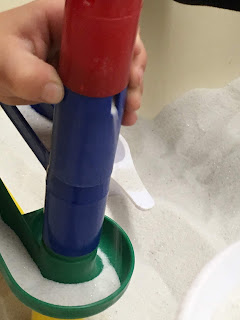

The children were instantly drawn to the familiar experience of building the marble run.

But they discovered that sand doesn’t move the same why that marbles do.

The sand didn’t flow quickly down the ramps. This led to figuring

out ways to move the sand more quickly - by pushing with fingers or wiggling

the whole tower to get the sand to flow down. Some of the children changed

their focus to filling the structure, using scoops and funnels and seeing how

much sand they could fill at a time.

They noticed the sand cascading over the top, and in some cases,

pouring quietly out of small cracks where the pieces fit together. The focus

shifted again to figuring out how to plug up those cracks, or alternatively,

how to make the sand flow out faster.

This set up held their interest for weeks. There was so much more to

sensory table play than just scooping, filling and pouring.