Over the past few years, I’ve been learning more about the

Reggio Emilia philosophy of education. This summer, I attended an excellent

two-day workshop called “Revisiting the Environment for Young Children”, which

focused on creating meaningful learning environments in preschools.

One of the things that sometimes disappoints me about

discussing “Reggio” with other teachers, or looking for resources online, is

how quickly teachers zero in on the aesthetics of the environment and reduce

the entire discussion to decorating ideas. “Where did you but those wicker

baskets?” “Look at the ideas for paint storage I saw on Pinterest!” “I’m

throwing out everything made of plastic and switching to wood!” But Reggio is

more than decorating. A child centered, child focused, meaningful classroom

environment isn’t just about beautiful baskets, natural light, and the color of the walls. It’s about the essential view that teachers hold about

children.

It’s about viewing the child as competent.

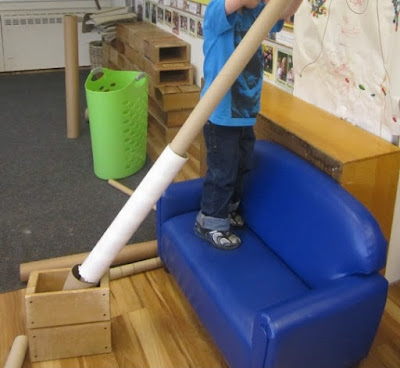

Once we get past the beautiful, artistically arranged

environment of Reggio-inspired classrooms, we see the messages that the

environment is sending. The classroom environment is set up to support children’s

choices. The baskets full of items that can be easily spilled, and easily mixed

up send a message that the children are trusted to choose what they want to

use, how they want to use it, and to be able to put it away again. The fragile

fabrics, plants, lamps, and arrangements of natural materials send a message

that children can figure out how to move through this environment without

causing damage, or, that if things are broken or knocked down, the classroom

community is capable of repairing them.

The arrangement of tables, chairs, and materials and the

schedule of the day suggests that children are capable of managing their own

time, decisions, and movement through the physical space, but also through the

daily routine. I’ve so often heard teachers use phrases like “good classroom

management is putting out fires before they start”. Reggio-inspired

environments don’t view children as potential fire starters, or as objects to “manage”.

They assume that children are competent to make decisions, and that the teacher

is there to work alongside the children, not to stand above “managing” them.

As I set up my classroom for the new school year, thinking

about materials, routines, and rules, I’m well aware of the limitations of

young children. But instead of focusing on the many things that young children can’t do, or that aren’t safe, or that

might be frustrating to them, I’m creating an environment that supports what

they can do, as competent children

acting on the world around them.