“It’s not your turn.”

“Stay in your own space.”

“Stop taking friend’s toys.”

“You have to share.”

So much of teacher’s time in preschool is spent policing:

telling children what they can and cannot do. And a lot of that policing

focuses on turn taking, sharing, and deciding who can play with what, when they

can play with it, and for how long. Many of the decisions are arbitrary and

exist simply because the teacher said so. Others may be rules that the children

supposedly decided on together – after much prompting and guidance from the

teacher to lead the children to create the rules that the teacher wanted in the

first place. A common theme in classroom rules that govern sharing and turn

taking is that they don’t involve children’s control or self-regulation, and

rely on a teacher, wielding the power and authority of adulthood, to enforce

them.

Sometimes so much time and energy is involved in enforcing rules about sharing

and turns, that it interferes with the activity itself. There’s value to social

negotiation (when the children are old enough to engage in it), but when more

time is spent waiting for turns or negotiating space than actually playing, I

sometimes wonder if this is the best use of the child’s time, or the teacher’s

time.

When there are multiple conflicts over materials and space, instead of focusing

on how to force children to change their behavior, it can be helpful to

re-examine your classroom environment to determine what the causes are of the

conflict, and what possible solutions there might be.

1.

Is there enough room?

Very often physical classroom space isn’t something we have

control over. The room is too small, or is designed in a way that makes it hard

to have functional classroom design. But within the space you have, how do you

use it? If the block area is the most popular area of the room, is there a way

to make it bigger? When you put out materials on a table, is there room for

several children to play without bumping into each other? When we tell children

to “stay in your own space” or “keep your hands by your own body” are we giving

them the space they need so they can do this?

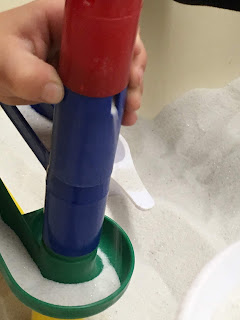

2. Are there enough materials?

So many classroom conflicts, just like conflicts in the

adult world, happen because there aren’t enough materials, or there aren’t

enough of the specific item that multiple children always want. If you notice

that day after day children are arguing over who gets to use the pink marker,

you might need more pink markers. If there aren’t enough magnet tiles to build

a tower, or enough sand for two children to each fill a bowl at the sensory

table, then the children’s time will be spent resolving the conflict, instead

of using the materials. There should be enough materials for several children

to use them, and multiples of popular items (like pink markers, lego wheels, or

whatever the children in your class tend to need a lot of).

3. How can you define space?

Knowing how to “stay in your own space” isn’t automatic –

it’s a developmental skill that takes time to learn. Creating individual spaces

where a child can easily see what materials they’re using, and know that their

space is protected, can help lessen conflict, especially for toddlers and young

preschoolers. Putting materials on individual trays or in individual bins, and

dividing up manipulatives and art supplies into individual stations can help

children find the materials they need and focus on their work.

4. How can you be more flexible?

Sometimes teachers are the ones who create the problems without realizing it.

When a teacher decides that only four children can play at the playdough table,

or that pretend food from the house corner can’t be moved into the block area,

that moves the teacher into the role of “traffic cop”, monitoring the classroom

to make sure that children and materials aren’t moving out of their designated

areas. And it increases conflict when following the inflexible rule becomes

more important than encouraging and facilitating play. If more children want to

play with playdough, is there a way to put some on another table? If one child

wants to join her four friends in the house area, is there a way to be

inclusive instead of leaving her out because “the rule is four people”? Can

materials be used in different areas of the room based on children’s interests,

to encourage the development of rich play and ideas?

Making space isn't only about physical space, it's about creating learning environments where children have the space to explore, create, and have ownership over their own spaces. Yes, there need to be rules and limits, but its the teacher's job to balance those rules and limits with what the children need to be able to play, learn, and grow.