I've heard so many comments from teachers worrying about children "making a mess", or teachers insisting that children put away one toy before taking out another. Children's play isn't divided into distinct parts. Children don't take out one toy, or one group of objects, stop playing, then put it away to begin anew with something different. Play is fluid and evolving and continues over time. Putting away materials in the middle of playtime stops the possibility of the child returning to and continuing their play, and stops opportunities for other children to extend on another's idea. Leaving the materials out for the entirety of playtime allows play to evolve and collaboration to happen.

Here is a series of pre-pandemic photos from one morning in my 2-3 year old classroom:

Early in the morning, two children took out the big blocks and built a large enclosure.

Explore Inspire EC

snapshots from my classroom and reflections on my journey as a teacher...

Sunday, December 5, 2021

Letting Play Evolve

Sunday, August 9, 2020

Making Room For Play 2020

Like many other preschool educators, I’ve spent these past months wondering and

worrying about what preschool will look like when we reopen. How do we maintain

the essence of early childhood education - children socially interacting and

playing with each other – while trying to maintain some physical distance between

children?

There isn’t an easy answer, and what teachers and

schools will be able to do will vary widely, depending on local regulations,

resources, community values, and school philosophies. As I’m thinking about how

to set up classrooms in a way that inspires play but encourages children to

keep some distance from each other, I realize this isn’t completely different

than things I’ve done before.

The key to setting up a classroom environment is intentional planning - using the physical environment as a “third teacher” to help guide, inspire,

and provoke learning. How we arrange furniture, materials, and toys influences

how children will interact with that space and those objects. Sometimes that

planning has involved ways to encourage children to space themselves out in the

classroom, and make room for play.

In the past, my planning focused on ways to reduce children’s conflict and

stress so that they could work and play constructively while building relationships,

and eventually be ready to share space and play cooperatively with peers. Now there are new reasons to give children

more room to play, but the strategies are still the same.

Often teachers plan a single focal activity for the

day – an art project, science experiment, or sensory experience that’s so

engaging that everyone wants to do it right away! Or teachers put out the new

manipulative or fresh batch of playdough and the entire class runs excitedly to

play with it. Instead of having a single attractive activity, multiple

interesting activities spaced away from each other can help children naturally

move apart from each other. If the brand new magnet tiles are on one end of the

room, and the fresh playdough is on the other, it’s easier for the children to

spread out and not play in the same space.

2. Define space

Some of my favorite teaching tools are individual trays

and bins. So much of children’s time in school is spent defending their space and materials from other children. For some children, worrying about someone taking their toy can become so

paralyzing that they can’t relax and play. Trays and individual work stations

define space, so that children can feel a sense of ownership, but can also be

set up to physically space children apart from each other.

3. Provide multiples of materials

As an adult, you wouldn’t want to have to share a pen

with someone else to take notes at a meeting. But we often set up this

situation for children – a child wanting to paint a rainbow needs to wait until

another child is done with the purple before putting on the final stripe. Having

enough materials means children can stay focused on their play, and feel secure

that they will have what they need. Having duplicate materials in individual

work space also limits the need for passing and sharing objects that might also spread germs.

4. Loose parts

Providing multiples of materials can be challenging. For store-bought materials, it might not be possible to have enough to set up individual spaces. Loose parts especially found and recyclable materials can be an easy way to split up materials. Bottle caps, rocks, sticks, shells, and beads are things there are many of. Sticks, leaves, pebbles, and other natural materials have the added benefit of being renewable – after play, they don’t need to be cleaned, you can just put them back outside and gather more.

5. Rethink your space

The biggest challenge in planning for this coming

school year is reinventing how we think of classroom space. Meeting needs for

distancing and cleaning might require rearranging traditional centers, removing

materials and furniture, and using space flexibly. I’m going to miss the scenes

of eight children building together in the block area, but I’m also thinking of

the times I separated the blocks into two piles, so children who were

struggling with cooperative play could build independently. Having two block

areas, or art centers, or a large multi-use space divided into smaller work

stations might be an option. Or rethinking how outdoor space or multi-purpose

areas could be used to in new and different ways.

There are no easy answers for preparing for this very different school year.

But some of the questions might not be as new as we think. Looking at ways that

we have helped children make room for each other before can help us think of

how to plan their space now, and might even lead to all sorts of growing and

learning that we didn’t even anticipate.

Monday, November 18, 2019

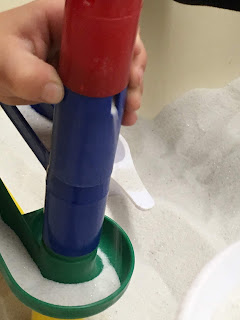

Marble Ramps in the Sand Table

Sunday, August 25, 2019

Letting Them Learn For Themselves

“What do you think the butterfly is doing?” I asked.

“And a larvae is another name for what?” prompted her teacher.

Of course there’s room for teaching facts, even though many of those facts can wait until children are older, and have had the chance to first observe, predict, analyze and evaluate on their own. When we introduce facts, we’re taking away opportunities for children to develop their own ideas, because once you know the “right” answer, there’s no more room for your own theories. When we substitute teaching facts for observation, we’re teaching children to trust what they’ve been told, not what they see for themselves. The well intentioned teaching act of giving background knowledge also teaches them to trust other opinions, especially authority opinions, before considering their own. In a world filled with competing narratives and an ever-increasing difficulty in determining what is true and what is not, children need to develop critical thinking skills that they can use to process information, not only based on their trust of the source, but based on their own experiences, thoughts and observations. We need curriculum and schools that don’t just teach children to say the correct answer, but that give them an opportunity to discover why that answer is correct, and to evaluate any other possible answers as well.

Monday, August 19, 2019

The First Days of School

Sunday, June 23, 2019

Helping Them to Put Ideas Into Action

Intentional teaching and scaffolding creativity are somewhere between those two points.

Wooden circles with letters written on them aren’t as open ended as plain wooden circles. Writing a letter, or number, or design on a piece of wood or a rock changes that object into something more specific. Objects painted with faces and costumes are dolls, just like any factory made doll that could be ordered from a catalog. There’s still plenty of ways that these materials can be used creatively, constructively, and interestingly, in classrooms - but as soon as the adult permanently makes the material into something else, some of the open ended possibilities disappear.

Tuesday, May 7, 2019

When Talking Gets in the Way

There are other times when talking just gets in the way of what they’re doing.

Even as we say that “children learn through play” and that we value “process over product” so much of teacher speech interrupts the child’s process and trying to lead the child to a tangible product. Often when a teacher says, “Tell me about what you’re doing” or “What’s your plan?”, it’s less about meeting the child where they are in the moment, and more about the teacher wanting information for themselves. Or just wanting to connect with the child who is at play, which is a wonderful goal, but requiring children who are immersed in process to answer adult questions isn’t always the best way to connect.

“I wonder what would fit inside those holes?” I asked.

She completely ignored me, and I felt a sense of discontent, that I had encroached on her process. The bolts were right there – she had been using them a moment before. If she wanted to put a bolt in the hole, she would have. She didn’t need me to tell her how to do it. Prompting her to “fit something” inside the holes was about me and my need to “teach” – not about her need to explore the materials through her own process.

Later, she put in a bolt, but didn’t push it down to connect the pieces. This time, I stayed silent, and allowed her to experience the process her way, without my interruptions.

Eventually, after putting together many pieces, moving them around, and taking some apart, she announced, “It’s a clock!”

and showed me how two of the wooden pieces moved like hands. She added small

metal pieces and said they were the numbers. After observing her entire

process, I don’t think she had a “plan” to build a clock, or to build anything.

For young children, the representational “product” often comes at the end of

the process. After completing the process of building, or drawing, or painting,

the child decides what their creation looks like, and labels it. The true

learning takes place in the process, and through the play of getting there. Sometimes

there are questions or comments adults have that can help them in their process,

but often, we just need to get out of the way.

Eventually, after putting together many pieces, moving them around, and taking some apart, she announced, “It’s a clock!” and showed me how two of the wooden pieces moved like hands. She added small metal pieces and said they were the numbers. After observing her entire process, I don’t think she had a “plan” to build a clock, or to build anything. For young children, the representational “product” often comes at the end of the process. After completing the process of building, or drawing, or painting, the child decides what their creation looks like, and labels it. The true learning takes place in the process, and through the play of getting there. Sometimes there are questions or comments adults have that can help them in their process, but often, we just need to get out of the way.